|

|

|

|

Unsettled Past - Unsettled Future

The Story of Maine Indians

June 2005 issue of The New England Quarterly

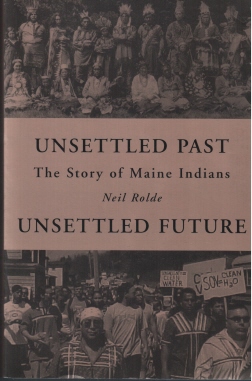

Unsettled Past, Unsettled Future: The Story of Maine Indians. By Neil Rolde (Gardiner, Maine: Tilbury House Publishers, 2004. Pp. xvi, 462. $20.00 paper.)

Neil Rolde’s Unsettled Past, Unsettled Future is well constructed and informative. It surveys the history of First Nations peoples living in what is now the State of Maine from the beginning of European colonization to the present. These peoples include four federally recognized tribes: the Aroostook Band of Micmacs, the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians, the Passamaquoddy Tribe, and the Penobscot Nation, all members of the Wabanaki Confederacy.

Having a genuine interest in the subject, and wanting some gaps in knowledge filled, I quickly agreed to review this volume. However, I must confess, I looked forward to the task as most people would to reading a boring operations manual. I was pleasantly surprised when I began reading, for Rolde, a former member of the Maine legislature who has written several other books on Maine history, has organized the historical facts in an interesting story format. He has also included useful illustrations and maps, and the text is well documented with reliable sources.

Unsettled Past, Unsettled Future is divided into twenty-six chapters. Chapter 3 sets the stage for the rest of the book, detailing the political and bureaucratic incompetence with which tribal treaties were handled after the American Revolution-an incompetence that eventually resulted in a financial and real-estate bonanza for Maine’s First Nations. The ensuring chapters focus especially on the political battles and intrigues that culminated in the historic 1980 Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act. This act gave the Passamaquoddy Tribe, the Penobscot Indian Nation, and the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians $81.5 million in trust funds and money for land acquisition in exchange for concessions, including giving up any further land claims (a separate 1991 settlement act included the Aroostook Band of Micmacs). This act, which has given Maine tribes the means to retain their dignity and become self-sufficient, will be cited by First Nations throughout the Americas as a precedent in future tribal land claim cases.

Rolde does an excellent job of chronicling the long series of events that led up to the settlement act, but his account is not without a few oversights. He questions, for instance, whether the European settlers engaged in genocide, asking, “Land theft, yes, but genocide?” (p.246). Uncountable millions of North and South American indigenous peoples were sold into slavery, killed by diseases that were deliberately spread, massacred by armies, starved to death, and so on. During the onslaught, many First Nations disappeared altogether, including several groups in Maine. Rolde’s conclusion that these horrific events can be blamed almost exclusively on the natural spread of European diseases needs to be revisited.

It is well documented, for example, that bounties for the scalps of men, women, and children were offered by the British in North America and, after the Revolution, by Americans for the express purpose of trying to exterminate such populations.

Although Rolde does mention a 1755 British scalp bounty proclamation issued to try to exterminate the Penobscot, he places the blame on the shoulders of Massachusetts Bay Lieutenant Governor Spencer Phips, not Governor William Shirley, and he portrays this proclamation as the exception, not the rule. In fact, Shirley himself had made a similar proclamation eleven years earlier. On 2 November, 1744, Shirley, after receiving a request from Nova Scotia’s Governor Jean Paul Mascarene for military assistance to help defend Annapolis Royal from a Mi’kmaq siege, responded by declaring war upon the Mi’kmaq and any other Wabanaki Nation assisting them. In his declaration he offered bounties for the scalps of men, women, and children. He then dispatched Captain John Gorham and his “Gorham’s Rangers” to Nova Scotia to enforce it. In 1749, Nova Scotia’s Governor Edward Cornwallis issued an identical proclamation with the stated intent of exterminating the Mi’kmaq (see, for example, John Stewart McLennan, Louisbourg from its foundations to Its Fall, 1713-1758 [1918; 4th ed., 1969]) .

When scalp bounties, starvation, and malnutrition failed to achieve the goal of extermination, both Canada and the United States, up until very recent times, vigorously pursued assimilation policies that were designed to achieve it, policies that Rolde mentions only briefly. Chroniclers of colonial history must be more forthright when writing about the cause of the decline of First Nation populations and cultures. Call it what it was: a deliberate assault motivated by greed that in many cases had extermination as the goal.

Rolde also gives little space to one of the most positive results of Maine’s land claims settlement, the enactment of a law mandating that Maine’s public schools teach Indian history. This law provides the means for the enlightened step of teaching about the atrocities that Europeans committed against the State’s First Nations peoples. Indeed, a state lesson plan includes a section on racism that states, “Over two hundred years ago, the Wabanakis faced the most serious form of racism-genocide” (see http://www.umaine.edu/ld291/MaineDirigo.pdf).

In spite of the stated shortcomings, Unsettled Past, Unsettled Future is an instructive read that will interest readers of American Indian origin and the general public in Maine and the rest of New England. Because it provides an exceptionally informative overview of a historic land claims settlement, it is also a must read for history buffs and lawyers.