|

|

|

|

CMM Logo

Prepared and posted April 2008

Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq - CMM - Development History

During late 1985, while employed by the Department of Indian Affairs, at its Halifax District Office as Nova Scotia District Superintendent of Lands, Revenues, and Trusts, I received several calls from my brother Chief Lawrence Paul, Millbrook Band, and my cousin Chief John Knockwood, Shubenacadie Band, requesting that I meet with them, and four other Chiefs, to discuss the possibility of me accepting a job as the founding executive director of a tribal council that they were considering forming. If I were to agree to participate, it would require me leaving the security of the Federal Public Service to create, implement, and manage the Tribal Council. The other four interested chiefs were: Chief Charlie Labrador

- Acadia Band, Chief Peter Perro - Afton Band, Chief Rita Smith - Horton Band, and Chief Roddie Francis - Pictou Landing Band. It was a perfectly feasible idea because such entities, although a new proposition for Atlantic Canada, were well established in other parts of the country, and were financially supported by Indian Affairs through its Tribal Council funding program.

From the beginning, via my phone discussions with John and Lawrence, I was aware that the rational behind their desire to create a Tribal Council was founded on their desire to have access to an organization that would have the capacity to research and promote the settlement of their land claims and other legal issues, plus have the capacity to provide administrative and financial advice, etc. to their Bands. These were services that they felt they were not getting from the existing provincial organization, UNSI, or Indian Affairs.

At first I declined to consider their request because I already had a good federal Civil Service job, with great pension benefits, which offered future security for me and my family. In contrast, they had absolutely nothing to offer - no funding, no security, no pension. The only positive was an opportunity to establish something that I had been advocating for the establishment of for a decade or so; a first class First Nation governmental entity that would be accountable, operate with transparency, and use responsible and sound administrative and financial practices.

Further, in addition to lack of security for my family, there was the prospect of overcoming two formidable obstacles that I would have to overcome to establish such an entity. First and foremost, many Department of Indian Affairs bureaucrats would try to impede its establishment in order to protect their self-interests from an organization that they would view as a threat to their security, secondly, opposition from some of the band councillors within the councils of the six bands involved, and band elected officials from other bands. The reasons such opposition could be expected from these sources were: I would be establishing an entity that would be viewed as a threat to the status quo that many Nova Scotia chiefs and councillors were quite content with, and many Department of Indian Affairs bureaucrats would view it as a threat to their future job security, because they were aware that tribal councils were meant to take over and administer many of the programs administered by the Department, eliminating the need for their jobs. In view of this, not something that a sensible person would lightly consider undertaking.

However, in spite of the negatives, I finally agreed to meet with them to discuss their desire to create an organization that would be called the Confederacy of Mainland Mi'kmaq. At the meeting, held December 3, 1985, at the Nova Scotia District Office in Halifax, I agreed to give it serious consideration and get back to them. That evening, I discussed the proposal with my wife, explained the negatives, and asked for her opinion. Her response was positive, “If its something that you want to do then you should do it.” Based on her support, I decided to give it a try.

Besides my wife’s support, there were two other factors that played a big part in helping me come to a favourable decision. The first, of course, was the challenge that the opportunity to be the architect of the Confederacy of Mainland Mi'kmaq presented, the other was a project that I had been secretly working on for three years, which was in direct conflict with the best interests of my employer, the Department of Indian Affairs, the Pictou Landing Band's Boat Harbour lawsuit. If it had become public knowledge that I was working on it with Tony Ross, the Band's legal counsel, God knows what the job consequences for me would have been. It was an uncertainty that had me nervously walking a tightrope since 1982. I don't know if DIAND would have fired me for it, it was a real possibility that they would, leaving my family without income, not a pleasant prospect. By accepting the offer, I would be in a position to work on it openly. Overview information about the case can be accessed at this URL: http://www.danielnpaul.com/ChiefRaymondFrancis-Pictou.html

The day after consulting with my wife, I contacted John and Lawrence and told them that I would do it. This led to us arranging a meeting at the Nova Scotia District Office for December 6, 1985, between Bill Cooke, Atlantic Regional Director of Indian Affairs, the Chiefs and myself. I must admit that during this period I was seriously doubting my sanity for involving myself in a proposal so fraught with danger for my family’s future financial security.

At the meeting, Mr. Cooke was very supportive, committing seed money, and he agreed to second me to the new organization until the end of March 1986, at which time I would have to decide whether to remain a member of the Federal Public Service, or resign to become a full time employee with CMM. With this commitment of support from the highest Departmental official in the region, I acquired office space at the Micmac Friendship Center on Gottingen Street in Halifax.

Thus, with a base to work from, I was set to begin the process of making CMM a fact of life. Fortunately, this was not my first experience with setting up an organization from scratch. During my employment with the Nova Scotia District Office of the Department of Indian Affairs, as Superintendent of Lands Revenues and Trusts, I was handed the chore of setting up the district office component for the Department's Reserves and Trusts Program. It included everything from setting up financial systems to writing job descriptions for five positions. This experience was to serve me well in overcoming the seemingly endless obstacles and roadblocks that were in store.

Note: At this time DIAND was closing it's Halifax District Office, and I was scheduled to move, April 1, 1986, to a managerial position with a Department then known as Manpower and Immigration. However, because CMM wasn't on stream as of that date, my new employer's regional director gave me a three month leave of absence without pay to decide if I wanted to move to his Department, or resign and continue as CMM's Executive Director. In May, I decided to close the door on my federal public service employment, I tendered my resignation.

With office space secured, a telephone installed, and a small budget at my disposal, my next chore was to acquire furniture and office equipment to work with. The Department of Indian Affairs donated some of its inventory of used furniture and equipment, and I purchased other used essentials at bargain basement rates from private entities. All in all, the collection wasn’t very impressive, however, I was satisfied that it was sufficient to allow me to get the development of CMM into full swing. I soon found out, as I had previously suspected, it was to be a daunting task. I had to be jack of all trades, working on a multitude of urgent diverse tasks at the same time. To enable the reader to appreciate the complexities involved in engineering such an organization from scratch, I'll list them, and provide an overview of problems encountered.

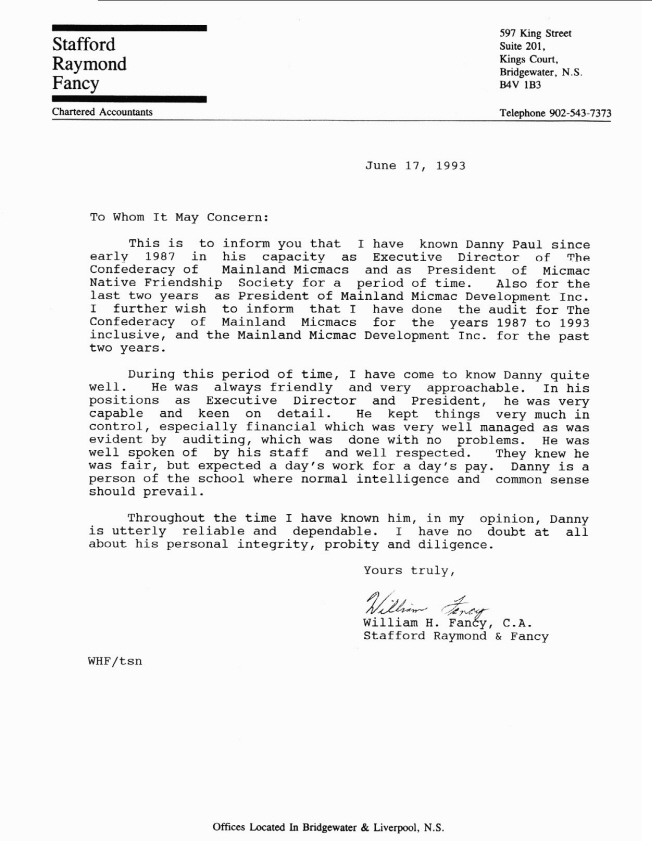

Sitting up a bank account for the organization was high priority. An easy task? Not by a long shot. During the 1980s banks were having a great deal of problems with the bank accounts of Band Councils and Indian organizations, which made them very reluctant to take on any more accounts from that source. After many tries, with discouraging results, I managed to persuade the Agricola Street branch of the Royal Bank of Canada, the one I did, and still do my personal business with, to open an account for the organization. The relationship worked fine. However, even with a good record during our stint in Halifax with the branch, when we moved to Millbrook later in the year, the Royal Bank in Truro would not open an account for us, nor would the Bank of Montreal, our last option was the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce. Drawing on the reputation I had for professional financial responsibility, which I had established in previous dealings with them on behalf of band councils, I was successful in persuading CIBC to take us on. From the beginning it was a mutually beneficial relationship. A copy of a letter from the Bank at the bottom of this page spells out its satisfaction with the excellent relationship.

The next high priority startup item was to staff a key position, clerk/typist and administrative assistant. I was well aware of a fact of life that many managers, to their sorrow, have not appreciated: to operate an organization professionally, a manager must have a fully qualified responsible person filling this key position.

However, this important chore, because of the urgent need to have a person on staff as soon as possible, was attended to in a rush manner - I hired an applicant without competition, or checking her qualifications. This misstep had its funny moment. The 1980s, being the time when computers and word processors were coming on stream fast, it never occurred to me that a person who applied for the job wouldn’t know how to use a typewriter. Luck being what it is, I had hired such a person. This became abundantly clear to me after I had passed her some letters to type - not hearing the typewrite in action, I looked out of my office and observed her staring at the typewriter as if it were a foreign object. I asked what was wrong, she responded that she did not know how to use what was in front of her, not even how to turn it on, she had never used one before. We had a good laugh about it, and she resigned. For a short period I got by on temps. When we moved to Millbrook, I was very fortunate to acquire the services of Barb Dorey, who proved to be invaluable in assisting me with the task of setting up CMM.

With secretarial/administrative assistant in place, I began in earnest writing a Constitution and by-laws for the organization. From the outset I intended to produce a document that would mandate that the Confederacy of Mainland Mi'kmaq utilize modern, responsible, and transparent administrative and financial practices in it's day to day operations. I knew from experience that a professional operational foundation for the organization was a must if it was to be managed responsibly, and productively, for the benefit of the member bands. Having the documents available was also an urgent need for another reason - DIAND tribal council funding regulations required that a tribal council, with a constitution and by-laws, be registered as a non-profit organization under the Societies Act of the province where it was located. Not having any funds to acquire legal assistance to help with this chore, I had to do it myself. Which, in retrospect, I must have done a decent job - standing the test of time, CMM’s constitution is still essentially the same in 2008, as it was then.

With the task of writing the Constitution and by-laws completed, and approved by the Chiefs, I tackled the task of getting the Confederacy of Mainland Mi'kmaq registered as a non-profit organization. This deed was not as easy as it may sound because the consensus among the Chiefs and myself, related to the special status of Indians and lands reserved for Indians, was that it should be registered with the federal government. I couldn't persuade the feds to do so in a timely manner, thus, as Indian Affairs was threatening to withhold funds if we didn't meet the funding requirement to register our organization as a non-profit entity, I reluctantly registered it with the Nova Scotia Registry of Deeds and Documents. The organization was officially registered December 5, 1986, coincidently, the day I was born in 1938.

Concurently with these organizational activities, we had to deal with the reluctance to join the organization by some of the band councillors from the Band’s of the Chiefs that wanted to create the Council, which, to say the least, was a difficult chore. However, within a few months, we had four on board, Horton, Millbrook, Pictou Landing, and Shubenacadie, but, because Tribal Council Funding Regulations required that a Council have a minimum of five, we needed one more. Finally, after much coaxing, Afton joined; we were off to the races.

In addition, while the before-mentioned was being attended too, I was engaged in moving CMM’s home office from Halifax to new accommodations in Millbrook, writing job descriptions for all the new (approximately 25 positions) administrative and operational positions that needed to be created and filled to operate the organization - research director, education director, engineering, support staff, etc., at the same time acquiring more office furniture and equipment to accommodate new employees as they came on stream. Interviewing applicants and hiring them was going on almost as fast I was writing job descriptions.

Also, in the midst of this dizzying activity, the most important and urgent task of all, one that was essential if we were to succeed, the acquisition of secure operational funding had to be attended too. Securing funds from some funding entities, such as land claim research funding was fairly easy, others, related to the bureaucratic obstruction I had anticipated in the beginning, was difficult. The following quote from We Were Not the Savages lays bare how some DIAND managers would nitpick to delay program turnover:

‘The threat the Confederacy posed to the comfortable situation of the bureaucrats caused them to raise obstructionist obstacles when the organization wanted to assume administrative control of programs. In early 1987, I was instructed by the Chiefs to begin consultations with the Department with the goal of CMM assuming management of the Department's post-secondary education program. The following is an excerpt from the condescending, paternalistic and racist reply of the Department's Regional Director of Education, Robert Pinney, dated January 14, 1987, to our request:

Subsequent to our discussion in my office on January 13th, I contacted my program people in Ottawa. They advised me that there are no administration dollars from the education program and that all your administration would have to be borne from the funds which you receive through formula funding.

I still get riled when I read this letter. After all, I had written CMM's constitution, so I didn't need the director's condescending interpretation of it. Despite his opposition, the Tribal Council eventually took over the program on behalf of the Bands, and still operates a very productive education program. “

All in all, attending to so many essential chores at the same time, made it a very hectic time. However, I was very fortunate, I had, as previously mentioned, acquired the services of a secretary with lots of experience to help, Barb Dorey. Without her making appointments, posting positions, etc., I would have been driven to distractionby by my hectic schedule.

In spite of the seemingly endlless turmoil, by the end of 1986 CMM was fully operational. The following are a few of the things that we accomplished by the time I retired in January 1994.

Number one accomplishment, and the one most important for the successful operation of the Confederacy of Mainland Mi'kmaq, an effective constitution and bylaws. I wrote the document in such a manner that it is a mandatory requirement that the organization be managed professionally, and with accountability and transparency. There are no loopholes to protect management from suffering legal consequences should they decide to appropriate some CMM funding for their own benefit. The need for such became abundantly clear during my negotiations for a long term funding arrangement with DIAND personnel, they wanted to insert "may," where there should be "shall," for accountability performance in the contract, which I flatly refuse to do. They stated it would be good to have the milder wording in place in case "something" happened that needed to be worked around. I rebuffed them with this simple statement: If I, or succeeding Executive Directors, should pilfer funds and get caught, then we must be held fully accountable, and suffer the full negative consequences.

Under the able direction of Donald M. Julien, a land and legal claims research unit, that was most productive was set up. It was so good that when I wanted an item researched, I would approach Don with the details and within a few days have the desired information in hand.

With the able and professional assistance of the late Kathy Knockwood, I established what has been described by education professionals as "a first class post-secondary education Program." The rules and regulations of the Program we developed have been adopted by many similar organizations across the country. Three years after the program was implemented, registration of students from the Confederacy’s six bands in post secondary education institutions went from approximately 20 to more than 200 students.

The band council advisory services I set up, under the able leadership of the professionals we employed, provided administration and financial, construction, economic developement, health, social assistence, and so on advice to member Band Councils on demand. And, I might add, were very effective and productive.

- started a collection of Mi'kmaq artifacts at the Confederacy offices that include ancient arrowheads, axes, dolls, snowshoes, and so on.

- instigated a drive which raised approximately $3 million for a new community centre for Indian Brook Reserve. Since it opened the Centre has become a major source of revenue for the Shubenacadie band.

- started a trust fund, set up for the specific purpose of addressing the future legal requirements of the six Bands associated with the organization. When he retired from CMM, January 1994, the fund had a balance of $140,000. This was the first undertaking of this nature by a First Nation organization in the Atlantic provinces.

Founded and became president of the Micmac Heritage Gallery. The Gallery was located on Barrington Street in Halifax and specialized in retailing the labours of Nova Scotia Mi'kmaq artists and crafts persons. It also retailed the artistic efforts of Native American producers from across Canada and the United States.

With the able and professional assistance of Rick Simon, I started a newspaper, the Mi’kmaq/Maliseet News, that is still being published. Readership, approximately 25,000.

Also, I was involved, on behalf of the bands, in political negotiations with federal and provincial governments. And, I was in charge of public relations, which I enjoyed very much. I had a lot of sucess in managing news media interviews to the extent that the end results were mostly very complimentary to our efforts to improve the prospects of our bands.

I offer my profound thanks and appreciation to all the Chiefs and employees who helped me make CMM a success. Without your help, it wouldn't have been possible.

Personal Consequences

Over the passage of time my decision to leave the federal public service has cost me dearly in monetary rewards, especially in pension benefits - well in excess of one hundred thousand dollars at this point in time, but I have no regrets. The satisfaction of knowing that I singlehandedly established the Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq, the initial First Nation Tribal Council in the Maritimes, which is still functioning and productive, and which has made a big positive difference in the lives of many Mi’kmaq, has made it all worthwhile.

In summary, during our lifetimes, the value of our personal achievements far outweighs the value of the money we earn while residing on Mother Earth. The feeling of satisfaction that one has when he/she looks around and sees that they have made a positive difference in the lives of their sisters and brothers is priceless. To have money enough to live on comfortably is important, but, as stated, it is of secondary importance to personal accomplishment. Therefore, I urge all First Nation Peoples, especially the young, to look for ways to help rebuild our First Nations. If we all work diligently for the goal of self-government, someday, somehow, it will be ours. The feelings of accomplishment and self-esteem that our Peoples will enjoy when that occurs will be tremendous, something that no amount of money can buy.

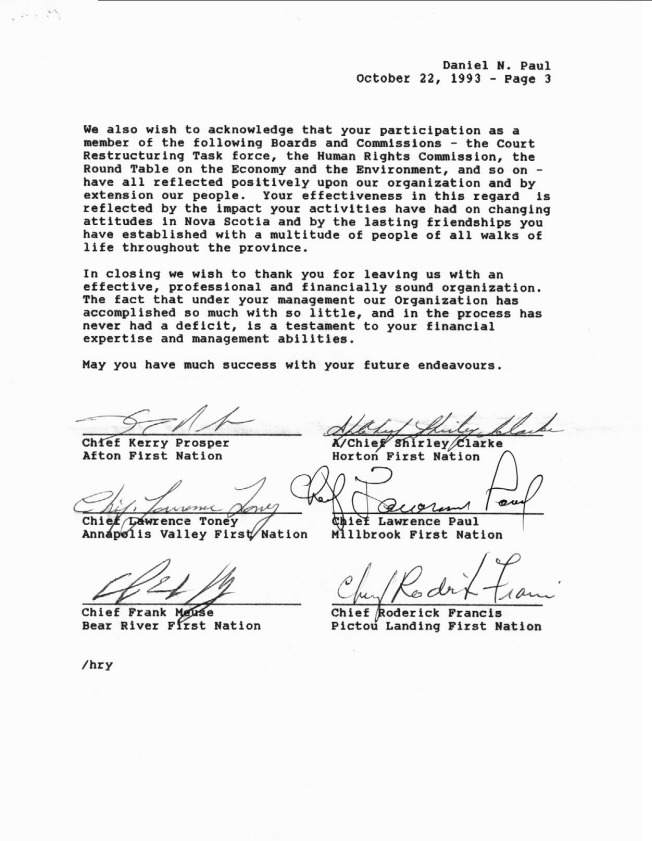

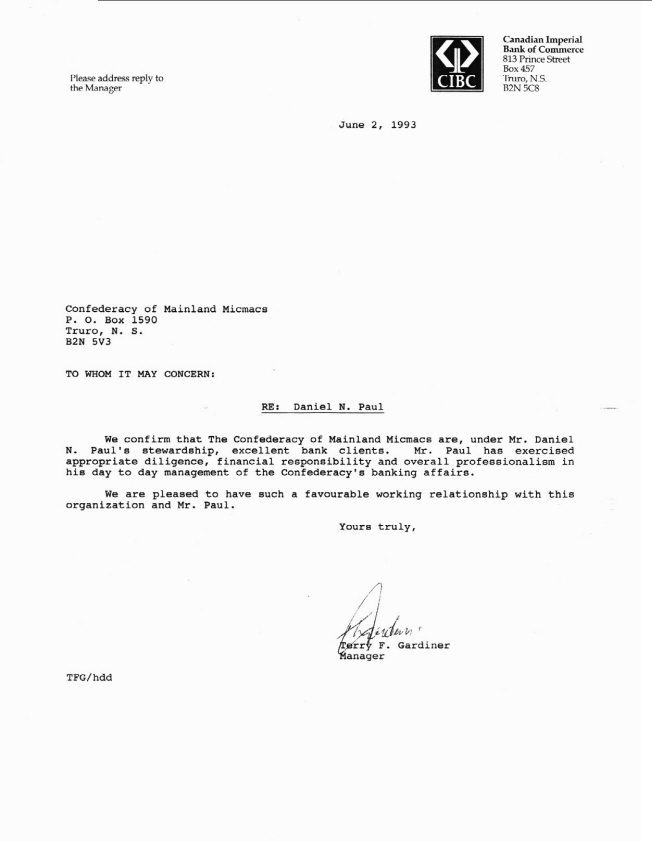

The following are copies of letters that I received upon my resignation in 1995, which acknowledge the fact that I had established one of the best operated Tribal Councils in Canada.

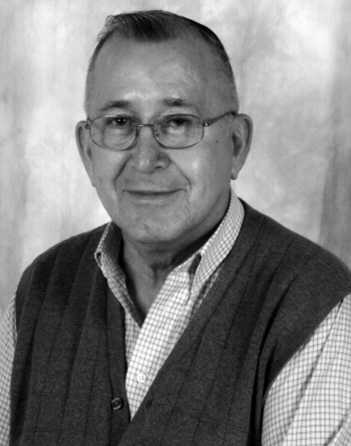

Top Row, Left to Right - Chief John Knockwood - Chief Charles Labrador

Chief Roddy Francis - Bottom Row, Left to Right - Chief Lawrence Paul

Chief Rita Smith - Chief Peter Perro - Executive Director Daniel N. Paul