|

|

|

|

Cree War Chief Wandering Spirit

NOTE: During this time in history members of First Nations across Canada were in various states of malnutrition and starvation. Traditional food supplies, and Indigenous trade, were disrupted to the point of being practically useless for survival purposes. Thus, the People were almost totally dependent on the mean spirited charity of the Canadian federal government for survival. Food rations did not include many items that were nutritious. Because of this the people were very susceptible to diseases, T.B. and other aliments were commonplace and took an annual deadly toll. Not surprisingly, caused by the rampant malnutrition, the Registered Indian population (Treaty Indians) remained almost stationery until the mid 1900s, when more nutritious diets and medical care started a population boon. For example, the Mi'kmaq went from around 1400 in 1948 to over 20,000 today, 2010.

The British set a goal in the 16 and 1700s for the eventually assimilation of all the country's Tribal Peoples. When Canada was created in 1867 by the British Parliament's enactment of the British North America Act, the new country adopted the mother country's goal of assimilation with dedication. Most programs and policies that it set up to manage the responsibilities that Section 91.24 of the Act mandated (the Section placed the responsibility for Indians and Indian lands at the federal level) were engineered, up until very recent times, toward solving the "Indian Problem" by assimilating the People into extinction.

It is my firm belief that the only reason that there wasn't far more eruptions of violent First Nations resistence during these years was that the People came to realize that they were outgunned, and if they tried for freedom, they would be brutally crushed. Therefore, as intelligent people, they accepted that they were at the mercy of what must have seemed to them a merciless invader, the English!

Daniel N. Paul, September 23, 2010

INTRODUCTION

Following the bloody events that occurred at Frog Lake in 1885, Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw (Wandering Spirit), war chief of Mistahimaskwa’s band, has been either vilified in the accounts left by the survivors and the apologetic statements of native leaders, or lionized in the oral traditions of a defeated people. Neither perspective is completely true. Ironically, this man, who began the killing at Frog Lake, has been condemned for his virtues, praised for his excesses. He was a warrior, caught in the dying traditions of his culture, unable to discard his upbringing and unwilling to abandon his responsibilities to protect his people.

The vilification began immediately after the killings at Frog Lake. Most of the condemnation fell upon Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear) whose reputation as a trouble-making chief had been widely reported in the newspapers since the late 1870s when he first refused to accept a reserve and insisted that he had not given up his land. Though Mistahimaskwa was ultimately held responsible for the attack at Frog Lake, the public quickly became aware that Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw had instigated the violence. In late 1885, when Theresa Gowanlock and Theresa Delaney published an account of the events at Frog Lake, their portrayal of Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw as a cruel savage became the accepted view in English Canada. In the decades that followed, their account influenced other writers who relied on this eye-witness report in order to add credibility to their own peripheral experience of the Frog Lake events.

The people of Canada, even western Canada, had little experience with men such as Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw. By 1885, most bands were interacting with the settlers in a manner that was generally peaceful, often docile and subservient. Weapons were used for hunting, not violence. Inter-tribal warfare was a thing of the past, kept in check by the North-West Mounted Police. Canadian bands, as opposed to their fierce American counterparts, seemed to have accepted the settlers and the government that represented them. From the point of view of the government and settlers, Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw’s attack at Frog Lake could only be seen as an anomaly, the actions of a rogue savage who, unfortunately, influenced some of the young men of Mistahimaskwa’s band.

Over-shadowed by the historical presence of Mistahimaskwa, Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw, for the most part, has been ignored. His one historical act was the killing of an unarmed man, an act in which the public, even in a time of war, could find no merit.

Among his own people, Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw has fared somewhat better. Many members of Mistahimaskwa’s band had been against violence from the beginning and would no doubt have blamed Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw for the suffering he had brought upon them. Others, however, found much to admire in him. As the events of Frog Lake became part of history, Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw’s violent attempt to win freedom for his people was idealized. Mistahimaskwa had the foresight to understand the futility of such an attempt. Without that foresight, Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw was a tragic hero at best, a man doomed by his personal history and an energetic will that could defy, but not defeat, the forces that were changing his world.

In attitude and belief, Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw was not unique. His opinions concerning the settlers and their government were similar to views widely held among the Cree and other tribes. There were, indeed, men who held more extreme views than his. His experiences were also similar, in a greater or lesser degree, to the general experiences of his people. As a warrior he was separated from other warriors only by degree, not by substance. Indeed, many Cree warriors found him too accommodating in dealing with the newcomers.

Much of his adult life was spent with Mistahimaskwa’s band but his experiences there differed little from the experiences of other bands. When food was scarce for Mistahimaskwa’s band, it was scarce in most locations and starvation was general. While members of Mistahimaskwa’s band threatened violence, such threats could be found wherever food was being withheld by over-zealous Indian Agents. Individuals might lash out in violence against the government’s agents but Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw was the first war chief to declare war.

It is not only the written accounts of the Frog Lake survivors that have distorted Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw’s character and legacy. Several other factors have created confusion and misunderstanding. Most historians have claimed that in the final days of his leadership Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw sought protection among the Woods Cree. The historians have taken their lead from the following telegram sent to military headquarters:

To Hon. A. P. Caron. From Toronto [June] 27th.

Despatch from Beaver River dated [June] 23rd says Wood Crees have “Wandering Spirit” a prisoner, and forty lodges are coming to the Mission here and will arrive in four days to surrender; few then left will likely disperse. (Signed) H. P. Dwight.

Using this telegram and remarks made by the hostages, historians have drawn the erroneous conclusion that Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw had abandoned his people.

The information in the telegram is false on several levels. First, the Woods Cree were as much Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw’s people as the Plains Cree. Also, there is evidence that suggests there were many other Plains Cree besides Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw travelling with the Woods Cree. Secondly, Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw was not a prisoner. General Strange, stationed at the Beaver River Mission, wrote the despatch that was delivered to Battleford where the telegram originated and the General, in his military mind, may have been the one to assume that Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw was a “prisoner.” But, if the Woods Cree thought Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw was dangerous or undesirable in some other way, they would either tolerate him, abandon him or send him away. They would not take him prisoner. Finally, the Woods Cree, or any other tribe for that matter, would not turn over to the soldiers one of their own people, no matter what he had done. There is no precedent in Cree history of the Cree willingly handing over one of their own for punishment by the government. The fact that neither Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw nor the Woods Cree came in to surrender “in four days” suggests that the information given to the soldiers was designed to throw them off the trail and give the Cree more time to escape.

Throughout his life, Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw had a strong sense of loyalty that extended beyond his band and tribe to include the Hudson’s Bay Company. He expected to find that same sense of loyalty in others. In the final tense month of his rebellion, his loyalty remained intact as he led a defeated people through difficult terrain and circumstances, remaining with them despite the punishment that awaited him.

This narrative does not attempt to provide a full understanding of the Cree culture that obviously moulded Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw’s character and beliefs. Many excellent books, such as David G. Mandelbaum’s The Plains Cree and John S. Milloy’s, The Plains Cree, Trade, Diplomacy and War, 1790 to 1870, provide detailed information on Cree daily life and cultural activities. A complete understanding of Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw’s complex character will have to await a biographer born and raised in the subtleties of Cree culture.

Most histories dealing with the Cree people, written by and for English-speaking Canadians, use the English version of Cree names. For the most part, this narrative uses Cree names but, because readers may be familiar only with the English versions, English names are included in parenthesis the first time Cree names are used. The English names can also be found beside the Cree names in the Index.

Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw did not understand English and had no affinity for the English sound “Wandering Spirit.” His name was pronounced “Kah pay pah muh tsuh kwayo.” W. B. Cameron who spoke both Cree and English records the name as “Kahpaypamahchakwayo.” Most modern references use a spelling similar to Cameron’s. However, in modern Cree spelling, “pay” is “pç” and thus, for the first time in print, his name appears here as Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw.

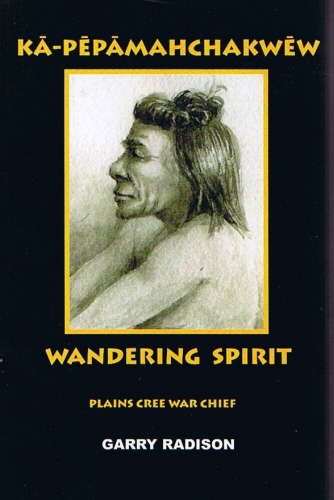

On the cover and on page 174 is reproduced Alexander Campbell’s 1885 drawing entitled “Wandering Spirt.” Though it is highly unlikely that Campbell knew Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw, his portrait of a calm, self-possessed individual seems, to this writer, more accurate than the sinister cartoon and verbal portraits that are usually associated with the war chief. Though Kâ-pçpâmahchakwçw tried to avoid the newcomers, their encroachment provoked confrontation and, therefore, they knew him mainly in moments of conflict. However, among his own people, he was a family man, a good citizen and often a pleasant, humourous companion.

GARRY RADISON is the author of five books of poetry. His poetic works have been described as “achingly honest...his unique voice, spare and muscular...resonates with the hard-earned truths of negotiating an unquiet peace with his prairie world.” (Hagios Press) The Saskatoon Star-Phoenix said his poems are “like guideposts in a vast desert.”

He has also written four works of non-fiction, two of which, Wandering Spirit: Plains Cree War Chief, and Fine Day: Plains Cree Warrior, Shaman & Elder, are his attempt to bring to life the history of the west from the point of view of the people who lived there.

Born and raised in Saskatchewan, he and his wife now live in Calgary, Alberta. He can be contacted at: radisongarry@yahoo.ca

More information about the Resistence can be found at the following addresses:

Chief Poundmaker:

Louis Riel:

Prime Minister John A. Macdonald's government oversees the mass execution of eight Cree:

President Abraham Lincoln's Administration permits the Mass execution of 38 Sioux:

Click to read about American Indian Genocide