|

|

|

|

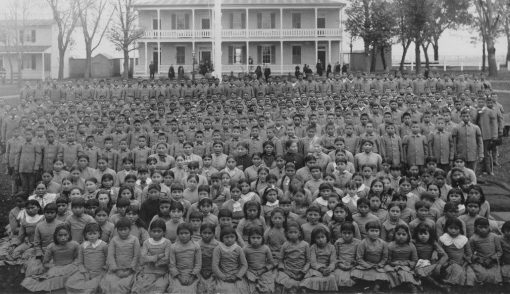

“Beginning in 1887, the federal government attempted to ‘Americanize’ Native Americans, largely through the education of Native youth. By 1900 thousands of Native Americans were studying at almost 150 boarding schools around the United States. The U.S. Training and Industrial School founded in 1879 at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, was the model for most of these schools. Boarding schools like Carlisle provided vocational and manual training and sought to systematically strip away tribal culture. They insisted that students drop their Indian names, forbade the speaking of native languages, and cut off their long hair. Not surprisingly, such schools often met fierce resistance from Native American parents and youth...The following excerpt (from a paper read by Carlisle founder Capt. Richard H. Pratt at an 1892 convention) spotlights Pratt’s pragmatic and frequently brutal methods for “civilizing” the “savages,” including his analogies to the education and “civilizing” of African Americans.“

Source: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/4929

In the middle of a bitter night in October 1879, a train puffed slowly across the last few feet of track and eased into Carlisle after a long journey from Dakota Territory. On board were 82 children from the Lakota people, whom most European Americans knew as the Sioux. Hungry and tired, they rose from their seats one by one, pulled their blankets tighter around them and stepped onto the small platform at the station. Their eyes, adjusting to the darkness, met a sea of strangers staring back at them. Just three years after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, hundreds of townspeople gathered with necks craned to glimpse the "exotic" Indian children from what was still regarded as the Wild West.

During the next 39 years, American Indian children became a familiar sight in Carlisle. While their arrival was little more than a curiosity to the townspeople, their departure from their homes, families and way of life marked momentous change in the lives of the children, their parents and their tribes.

From 1879 to 1918, approximately 12,000 Native-American children attended the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, on the grounds of Carlisle Barracks, to become educated in the ways of European-American culture. They came from all corners of the United States - some even from Puerto Rico and the Philippines - and from more than 140 tribes. Some came willingly; others did not. And while many survived, some did not.

The goal of the Carlisle school and its founder, a U.S. Army officer named Richard Henry Pratt, was total assimilation of Native Americans into white culture, at the deliberate cost of their Indianness. The legacy of Carlisle, and of the extensive system of boarding schools it spawned, continues to pervade the lives of Native Americans today. Mention the Carlisle Indian School in Central PA, and most residents think of Jim Thorpe, its most famous student. Proclaimed the world's greatest athlete, Thorpe became a source of pride for the school and the town. But to most Indians, the mention of Carlisle elicits a conflicting mixture of strong emotions - both positive and negative - involving the dignity of survival and the mourning of lost cultural identity.

More than 80 years after the school closed, the Cumberland County 250th Anniversary Committee has invited each of the 554 federally recognized American Indian tribes, along with the nonnative community, to come together in Carlisle for the first-ever commemoration of the school and its contradictory legacy. Powwow 2000: Remembering Carlisle Indian School will take place on Memorial Day weekend on the site of the former school. The organizers hope "to provide awareness of Native-American Indian cultures and the Carlisle Indian School history, and to remember and honor the students who attended the school."

But there's also a deeper purpose to the singing and dancing, the ceremonies and talks. Pulitzer Prize-winning Native-American author N. Scott Momaday, the keynote speaker for the event, hopes "it is a healing process. We are doing real reverence to the children."

Captain Pratt's dream

"Convert him in all ways but color into a white man, and, in fact, the Indian would be exterminated, but humanely, and as beneficiary of the greatest gift at the command of the white man - his own civilization."

- Characterization of Carlisle Indian School founder R.H. Pratt's

philosophy by historian Robert H. Utley, 1979

The history of the Carlisle Indian School is inextricably linked with its founder. R.H. Pratt, a US Army captain, had commanded a unit of African-American soldiers and Indian scouts in Dakota Territory for eight years following the Civil War. Subscribing to the ideas of the "Indian reformers" of the time - many of whom were Quakers and Christian missionaries - Pratt believed the solution to the so-called "Indian problem" was not separation, which was the function of the reservations, but assimilation.

Pratt believed the best way for Indians to be absorbed into mainstream American society was to provide them with an education. In 1875, Pratt was assigned to guard a group of Caddo, Southern Cheyenne, Comanche and Kiowa prisoners at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. He selected a group of these prisoners to test his hypothesis about Indian education and sent them to the Hampton Institute in Virginia, then a boarding school for black children. The 17 students adapted so completely to European-American ways that Pratt decided he wanted an all-Indian school of his own.

In 1879, the Army gave Pratt permission to house his school on an old cavalry post in the small, rural town of Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He traveled west to recruit his first students from Rosebud and Pine Ridge, two Lakota reservations in what is now South Dakota. In the meantime, two of Pratt's former pupils from Hampton were recruiting Cheyenne and Kiowa children for Pratt in the Southwest.

Meeting with well-known and influential Lakota chiefs and elders - Spotted Tail at Rosebud and Red Cloud at Pine Ridge - Pratt argued that had their people been able to understand English, they might have prevented the loss of land and freedom that had occurred with the institution of the reservation system, or at least understood what was to come.

Though Red Cloud and Spotted Tail were skeptical of Pratt's intentions, they believed their land and resources inevitably would continue to be purloined by the white men. Each chief sent 36 children with Pratt, including five of Spotted Tail's own children and Red Cloud's grandson. According to Pratt's account, 10 more were added to the group as it made its way to the steamboat for the first leg of the journey.

Collective wail

"In our culture, the only time we cut hair is when we are in mourning or when someone has died in the immediate family. We do this to show we are mourning the loss of a loved one."

- Sterling Hollow Horn (Lakota), Pine Ridge, South Dakota, 2000

As the train carrying the first group of Lakota students made its way across the country, townspeople came to every train station to gawk at the children wearing their blankets and moccasins. To avoid this spectacle in Carlisle, Pratt routed the train to a tiny depot several blocks from the main station on High Street. His plan was foiled, and hundreds of cheering Carlisle residents were waiting on the platform. When the travelers arrived at the school, Pratt was enraged to find that the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs had failed to send provisions, bedding or food. The children were forced to sleep, hungry, on the floor in their blankets.

Pratt immediately left to collect the Cheyenne and Kiowa children, and his wife and the teachers took charge of the first wave of assimilation. The process began with the outward signs of Indian appearance - clothing and hair. Confused and homesick, the Lakota children wept as their long hair was cut and fell to the ground. On one of the first nights after the Lakota children arrived, a collective wail rose up from their throats, its wrenching sound echoing across the campus. What they did not yet know was they were mourning the shearing of their cultural identities.

Tools of assimilation

"God helps those who help themselves."

- Slogan on the masthead of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School newspaper

Because Pratt wanted his charges to learn trades as well as academics, half of each day was devoted to reading, writing and arithmetic, and the other half to trades, such as blacksmithing and carpentry for the boys, sewing and laundry for the girls. The entire system was shaped by Pratt's military past. Boys dressed in uniforms, and girls wore Victorian-style dresses. The students practiced marching and drilling and were given military-style ranks.

One of the few original structures still standing on the grounds is a haunting reminder of the school's rigidity. Built in 1777 to store gunpowder, the guardhouse contained four cells in which children were locked up, sometimes for up to a week, for various indiscretions. Running away was a common offense.

In addition to their vocational and academic pursuits, the Indian children also studied the humanities. Pictures in the students' sketch books chart the progress of assimilation. When they first arrived, children drew things they remembered from home, such as buffalo hunts and warriors counting coup on horseback. In time, the drawings evolved into representations of their new lives - including images of farms and children with short hair wearing European-style clothing.

Mohican composer Brent Michael Davids, who is performing at Powwow 2000, has studied the use of music as a tool of assimilation. Though the children came from backgrounds rich in song, they had no concept of European approaches to music. "The students sang songs at mealtimes in a four-part harmony," Davids explains. "It was a completely different singing style. The hymns they were forced to sing were the Western style, espousing the values of being good Christians."

Nearly 120 members of Davids' Stockbridge Mohican clan attended Carlisle. He learned about them while composing music for a CD-ROM about the Indian School. "[Carlisle] was a missing link for me," Davids says. "I knew they tried to kill us, then herded us onto reservations, but I couldn't figure out how we cut our hair and started wearing shoes."

Theater also was used to indoctrinate the students in the customs of white America. Lynne Allen, an artist who lives in Furlong, Pennsylvania, remembers finding a photograph of her Lakota grandmother, Daphne Waggoner, performing in a Thanksgiving play at Carlisle. "Indians dressed as Pilgrims and Indians dressed as Indians," Allen says, laughing at the irony of Native Americans portraying stereotypes of themselves.

Language lost

"When you destroy a person's language, it destroys their world view. They're left with only fragments. I speak Spanish, and I speak English. When you think in Spanish, it's totally different. When they leave the school and go back to the reservation, they're still Indian, but not anymore."

- Jorge Estevez (Taino), participant coordinator, Museum of the American Indian, New York, 2000

The destruction of native languages was one of Pratt's main objectives. Children began English lessons as soon as they arrived at Carlisle. Students were punished, sometimes severely, if caught speaking their native languages, even in private.

According to Tsianina Lomawaima, a professor at the University of Arizona and author of a book about the Chilocco Indian School in Oklahoma, Carlisle and other boarding schools modeled after it didn't instantly eliminate native languages. But because of their school experiences, many former students decided not to teach these languages to their children.

Sterling Hollow Horn, 38, who works at KILI, a Lakota-language radio station on the Pine Ridge Reservation, had several relatives who attended Carlisle and has witnessed this in his own community.

"They didn't let [the students] speak in the old language," says Hollow Horn, a member of revered leader Crazy Horse's band of the Lakota people. "They set a dangerous precedent. I'm fluent in the Sioux language. Most people my age don't speak the language. It's dying out. The whole spirituality and way of thinking is intertwined with the language. That's all being lost. Carlisle was the starting point for this."

In 1995, Ed Farnham, a major in the US Army, learned he was being transferred from his base in Germany to the Carlisle Barracks. Originally from upstate New York, Farnham was excited he would be living closer to his family. When he called his mother to tell her, she asked him, "Don't you know what that place is?" Only then did he realize he would be living in the same Carlisle that had been the subject of murmurings in his family.

Farnham's grandmother, Mamie Mt. Pleasant, attended the Indian School for nearly a decade. A Tuscarora Indian, she was 14 when she was sent to Carlisle. Mamie's older brother Frank had been one of the school's star athletes in football and track and field. When Mamie came to Carlisle in 1908, Frank was in London as a member of the US Olympic track-and-field team, but was unable to compete in the broad jump because of a torn knee ligament. Before she graduated from Carlisle in 1917, Mamie learned to sew and was rumored to have been courted by another Carlisle athlete - Jim Thorpe.

Though he grew up across the street from his grandmother on the Tuscarora reservation near Niagara Falls, New York, Farnham was never taught the Tuscarora language. After Mamie Mt. Pleasant returned to the reservation from Carlisle, the only time she spoke Tuscarora was at night, praying Christian prayers before bed.

'The man on the bandstand'

"Kill the Indian, save the man."

- R.H. Pratt, often-repeated catch phrase

Pratt wrote extensively and candidly about his reasons for founding the Carlisle school. He referred to relations between European and Native Americans in terms of the "Indian problem" and compared it to a similarly widespread attitude toward the "Negro problem." In 1890 he wrote to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, "If millions of black savages can become so transformed and assimilated, and if, annually, hundreds of thousands of emigrants from all lands can also become Anglicized, Americanized, assimilated and absorbed through association, there is but one plain duty resting upon us with regard to the Indians, and that is to relieve them of their savagery and other alien qualities by the same methods used to relieve the others."

Pratt may be considered a bigot by today's standards, but his views of African Americans and Indians were considered progressive 100 years ago. He and most people who regarded themselves as advocates for Native Americans considered Carlisle a "noble experiment." He believed that education was the only way native people would survive - at a time when the survival of Indians was a goal that a significant number of white Americans did not support.

Pratt was often referred to as "the man on the bandstand." Located directly in the center of the school's campus, the circular bandstand provided a view of the entire grounds. But more than a pseudonym for Pratt, the constant reminder that "the man on the bandstand" was watching represented the all-encompassing, paternalistic way in which Pratt and the teachers, ministers and matrons viewed themselves as the "saviors" of the Indian children. The phrase was meant to make the children feel secure and cared for. It also reminded them that they were under constant surveillance.

Tsianina Lomawaima believes, in some ways, Pratt was unusual for his era. "His commitment to those students as individual human beings was unique," she says. "He really believed in them. He fought for those kids. The part of Pratt that wasn't unusual was that he didn't believe Indian culture would survive, or should."

Legacy

"There were kids who were Lakota, and there were kids who were Wampanoag. At Carlisle, they became Indian."

- Barbara Landis, Carlisle Indian School biographer, 2000

The erosion of Native-American sovereignty was swift and unrelenting. Propelled by a hunger for land, gold, power and control, it swallowed up everything in its path, including communities, languages and religions. No matter the Nez Perce were distinct from the Navajo, the Seneca from the Seminole, the Coeur D'Alene from the Crow. They were one in their difference.

Repercussions of the Carlisle Indian School experience are still felt today, often in unsuspected ways. In March, National Public Radio reported that Native Americans were the most undercounted ethnic group in the US Census, in part because older members of the "boarding-school generation" remember that when they gave their names to government agents, they were "carted off involuntarily."

Most of the 2 million Native Americans living in this country have some sort of biological link to Carlisle or one of the boarding schools created in its wake. There is also a shared sense of inner conflict. It is difficult for many Indian people to fully condemn or condone Carlisle. But they agree the disintegration of Indian cultures and the arrogant racism toward native people is horrific.

Much of the inner turmoil Carlisle has spawned revolves around the question of what the lives of native peoples would have been like without Carlisle and similar boarding schools. Barbara Landis, who researches the Indian School for the Cumberland County Historical Society, points out that the children's lives were less than idyllic before they came to Carlisle.

"It was just about the end of the treaty-making era," Landis explains. All the major battles between Indians and the US military were over except for the massacre at Wounded Knee, which would take place in 1890. But the children would have had some memory of the wars, in which their parents and grandparents had participated.

"The only place for Indians was in the agency [reservation]," Landis says. "Emotionally, the structure of their world changed with the agencies, the rations, a whole new way of eating, not being able to hunt buffalo."

"Most people around here are proud their children and ancestors went there," Sterling Hollow Horn says of the Carlisle Indian School. "But four- and five-year-olds were being taken from their families. There was a lot of confusion from parents, but more so from the children. Carlisle was good, and it was bad. It depends how you want to look at it. I personally think it was good. It showed Indian kids were intelligent. But I know a lot of people would disagree with me."

Ed Farnham has only begun to wrestle with his feelings about Carlisle. "It's a touchy subject," he says. "On the one hand, you had all these Indians coming together to play football and being a dominating force. That was great, and that never would have happened [otherwise]. But losing or suppressing your cultural identity, that's not good.

"I know things would have been different if my relatives hadn't come here. My grandmother wouldn't have been a seamstress. My uncle wouldn't have gone to Europe and done all he did."

Though her grandmother described her time at Carlisle as pleasant, Lynne Allen feels boarding schools contributed to her own confusion about cultural identity. Though Allen is a descendant of Chief Sitting Bull, she is only one-sixteenth Lakota - not enough to be officially recognized by the tribe as a member. "Being part Indian and not belonging anywhere was something [my mother] carried with her her whole life," Allen explains. "It's something she passed on to me, this feeling of being marginalized.

"Part of me knows it helped a lot of people survive in the world. But there were people who stayed on the reservations and survived, too. It was the age, it was the era of missionaries and zealots trying to 'help the savages.' ... I don't know what would've happened if they wouldn't have done that."

A time for healing

"My lands are where my people lie buried."

- Crazy Horse, Oglala Sioux leader, 1877

When you are driving on Claremont Road in Carlisle, it's easy to miss the small, tidy cemetery along the side of the road. The long, slender limbs of a weeping-cherry tree in the nucleus of the plot reach down like fingers brushing along the arched tops of pristine, white tombstones surrounded by a short, iron fence. Row after neat row of graves dot the grass.

The Indian cemetery is one of few traces of the school left in Carlisle. More than 175 tombstones line the ground. Prayer cloths, strings of shells and beads and small bundles of sage and sweetgrass embrace the tree trunk.

The realization is harsh and unforgiving - there are children buried here. They died of the diseases that killed many children in those years, regardless of ethnicity. Climate change, separation anxiety and lack of immunity also contributed to the toll. Most were sent home for burial, but some had no relatives who could have made the arrangements, or their homes were simply too far away. Because of fear of infection, tuberculosis victims were buried immediately.

Most of the town of Carlisle's connection to the school revolves around its legendary football team and Jim Thorpe. In the All-American truck stop just outside of town, there's a wall covered with framed photographs and newspaper clippings of Thorpe. A memorial stone in the town's square pays tribute to him. Wardecker's, a men's clothing store on Hanover Street, which at one time extended a special line of credit to the Indian School's athletes, houses a shrine of photographs of Thorpe, Coach "Pop" Warner and the football team. Carlisle High School's mascot is a buffalo, and its nickname is the Thundering Herd.

But Native-American memories of the Carlisle Indian School run much deeper. Beverly Holland, who lives in Harrisburg, moved to Central Pennsylvania about 20 years ago from the Yankton Lakota reservation in South Dakota. Her grandfather attended Carlisle for nearly four years. But, like Ed Farnham, she didn't make the connection that she was living so close to the former school.

"I didn't run right to the school after I found out," she says. "It was a long time before I could visit the cemetery. I think I visited there about four or five times before I could stop crying."

It was equally moving for Farnham. "I had no idea what happened there," he says. "I was ignorant." But when he visited the grounds for the first time as a soldier, he acknowledges a complete reversal of attitude. "It was almost a spiritual event for me, once I understood that's where my grandmother walked for so many years," he says. "She was Christian. I know she would've gone to the chapel. The foundation of the chapel was about 200 yards from where we were housed. Kneeling on the ground [in the cemetery], looking at the graves, you just have ... more of a reverential attitude."

Sacred ground

Powwow 2000 will doubtless be an emotional time, but the members of the organizing committee, comprised of about half native and half nonnative members, hope the event will help salve the unrelenting pain felt by so many.

Nadine West, a Chippewa Indian and member of the powwow committee, has made an annual pilgrimage from her home in Harrisburg to the Indian cemetery each Memorial Day for years. She claims the decision to schedule the powwow during a national holiday of remembrance was deliberate and symbolic. "Those children in that cemetery are our veterans," she says.

Originally from the Cheyenne River Lakota reservation in South Dakota, Carolyn Rittenhouse of Lancaster joined the powwow committee after realizing the impact of the school on Lakota children. They were the first students to attend the school, and more than 1,100 of them went to Carlisle throughout its tenure, including her great-uncle, Thomas Hawk Eagle. Four generations removed from Carlisle, Rittenhouse's daughter Danielle, 9, plans to dance the jingle-dress dance at the powwow.

Rittenhouse believes the powwow also will be a positive experience for non-Indians. "The nonnative community will be educated when they attend - seeing the dancing, eating the food, hearing the stories - so healing can begin for them, as well," she claims. "The event won't only impact native people, but the whole community."

Since the closing of the Carlisle Indian School, the descendants of its students and the descendants of the community into which they were to be assimilated have never come together to consciously honor he students' memory. It is significant that when they do so this month, the commemoration will take place on the ground where the tears of those first akota children fell 121 years ago.

"I hope that everybody there has a sense of the sacrifice that the children made," says keynote speaker N. Scott Momaday. "Sacrifice is related to the word 'sacred.' It is a sacred place because of the sacrifice made by the children."

Stephanie Anderson is the former managing editor at CENTRAL PA magazine in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

At present she is a fulltime graduate student at Penn State University - working to earn a Master's of Fine Arts in creative-nonfiction writing. The thesis Stephanie is working on is essentially the first draft of a book -- about 150-200 pages of a completed nonfiction manuscript - about the Carlisle school. Her intent is to have included a mix of history and personal narrative - with family members of former Carlisle students recounting their relatives' experiences, and what impact Carlisle had on their families. She is looking for people to interview about the subject. Her particular interest is in the loss of language.

If you have information about the school that you would like to share with Stephanie she may be reached via e-mail at. sna113@psu.edu

For an overview of Canadian Indian Residential Schools Please Click: http://www.danielnpaul.com/IndianResidentialSchools.html

"On Scared Ground" can also be viewed at: http://www.wordsasweapons.com/indianschool.htm

"Let all that is Indian within you Die" Shocking reading: http://www.twofrog.com/rezsch.html#statement

Click to read about American Indian Genocide

by Stephanie Anderson

As published in CENTRAL PA magazine, May 2000