|

|

|

|

Gov. Edward Cornwallis Scalp Proclamation 1749

NOTE: The following is what Robert Jackson, chief American prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials, had to say about genocidal behaviour:"

"No regime bent on exterminating another peoples will describe their intent in so many words, since such intent is imbedded in the very operation of the system of extermination. On the contrary, the actions of the agencies of murder are enough proof of such intent, and therefore when the transporting of people into the conditions of disease and death is condoned and facilitated by a government, and when these crimes are concealed from the scrutiny of the world of the same government or other agencies, it can be safely asserted that this regime intends to annihilate the targeted people and is guilty before the world of crimes against humanity."

Bassam Imam: February 1, 2011

Any person who believes in a just GOD, a person with an atom's worth of dignity and morality, would rename Cornwallis Park. He, Cornwallis, ordered the extermination of full-fledged human beings like us who had a GOD-given right to live on their own lands justly, peacefully, and without being slaughtered, persecuted, tortured, unjustly demonized or otherwise treated badly.

The following short bio about the life and career of Edward Cornwallis, the British Colonial Governor of Nova Scotia, the author of the infamous 1749 proclamation for Mi’kmaq scalps, which offered a bounty for the scalps of men, women and children, will assist the reader in appreciating the barbaric bent of the Governor before reading the Proclamation Document.

By JON TATTRIE

Halifax Chronicle Herald, March 11, 2012,

The sixth son of an aristocratic family, Halifax's founder met shame and failure later in life.

WHEN CORNWALLIS Junior High was renamed Halifax Central Junior High earlier this year, I felt opinion swelling in my throat. From my front-row seat as a journalist, I have covered the controversy over Halifax's founder, Edward Cornwallis, from naming a school after him to erecting his statue.

Opinion bubbled up to my lips and was about to spew into the world when a little voice in my head asked me: What do you actually know about this man?

I could think of a few things: he founded Halifax in 1749 and he issued a scalping proclamation against Mi'kmaq people. And that he . . . Um. He was born in . . . Er. How long did he live in Nova Scotia? What else did he do? Uh . . .

I felt the pinprick of fact deflating the bubble of opinion. I figured before I judged the man, I should at least get to know him. I headed to the Nova Scotia archives and the Halifax Public Libraries and spent the next few months reading the letters Cornwallis wrote and received in Halifax, the minutes of his council meetings, and the handful of articles and books containing references to him.

Surprisingly, no one has written his biography.

Cornwallis was born in England in 1713. He was the sixth son of Lord Charles, the fourth Baron Cornwallis, and Lady Charlotte Butler, daughter of the Earl of Arran. His family was rich and influential. In addition to expansive estates in Suffolk, they kept a house at 14 Leicester Sq. in London.

His first job came at 12 when he and his twin brother Frederick were appointed royal pages to King George II. "This little appointment . . . explains why the Hon. Edward was so well looked after in later times of great emergency and difficulty," writes historian James MacDonald in an 1899 paper.

Cornwallis studied at Eton College and entered the military in 1730. Lingering in London garrisons, he became a lieutenant, then captain, then major. He took the family's seat in Parliament when his older brother died. "Up to this date, Cornwallis appears to have lived in an atmosphere of court favour and officialism," MacDonald says.

The first "difficulty," as MacDonald put it, arose from his service in 1745 at the Battle of Fontenoy. Cornwallis's commander died at the start of the Belgian fight and Cornwallis was put in charge. The battle was a disaster for Britain. Some 2,000 troops died, including 400 under Cornwallis's command. The best historians could make of it was that Cornwallis helped with the retreat. The streets of London greeted the army with scorn.

Despite the setback, Cornwallis won a prestigious post as groom of the king's bedchamber.

In 1745, he was placed in charge of a regiment dispatched to the Scottish Highlands. The Jacobites under Bonnie Prince Charlie had raised a massive army and advanced to the outskirts of London before retreating to Scotland. Cornwallis was part of the British forces sent to crush the rebellion.

The final battle came April 16, 1746, at Culloden. The professional British soldiers quickly routed the rebel Scots and killed 2,000 Highland warriors before pursuing them off the battlefield. The slaughter that followed was called the Pacification.

It became illegal to wear a kilt or tartan and an offender could be summarily executed. The ancient clan system was to be dismantled by force.

Cornwallis was in the thick of it. Michael Hughes fought with him and wrote a tract called A Plain Narrative and Authentic Journal of the Late Rebellion. It tells how Cornwallis led 320 men to destroy the house and lands belonging to a rebel leader.

Hughes notes Cornwallis's "great humanity and honour" during the systematic hunting down of any man, woman or child displaying any Jacobite sympathies. Such "traitors" were shot dead or burned alive in their homes. Properties were looted and claimed for King George. Patrols were sent "rebel hunting."

"From hence the party marched along the seacoast through Moidart, burning of houses, driving away the cattle and shooting those vagrants found about the mountains," Hughes writes. The army returned in glory to London.

The historian MacDonald says 1748 found Cornwallis in poor health and his regiment in a "mutinous state." He resigned his command. His benefactor George Montague Dunk, Lord of Halifax, secured him a job as governor of Nova Scotia.

The Fortress of Louisbourg was being returned to the French and Britain needed a fortress to offset it. To that end, Cornwallis was dispatched to found Halifax in the spring of 1749.

The site he selected was in Mi'kmaq moose hunting territory and the sawmill that followed at Dartmouth sat on their vital water highway, the Shubenacadie. Both sides made overtures of peace but both sides clashed. Mi'kmaq warriors, outgunned by the soldiers, launched a guerrilla campaign to contain the English.

Cornwallis saw only one solution. "Without force and without money, nothing can be done," he wrote. London urged him to engage the natives in trade and keep the peace with France, but Cornwallis did not trust the restive province.

He fretted constantly that the Mi'kmaq and their French allies would destroy the nascent settlement. He sent soldiers and the infamous Rangers into the woods to drive them away. Newborn Halifax was heavily fortified.

In October, he issued the scalping proclamation. "To declare war formally against the Micmac Indians would be a manner to own them a free and independent people, whereas they ought to be treated as so many banditti ruffians, or rebels, to his majesty's government," he wrote.

Cornwallis implemented the tactics of the Scottish Pacification: terror, brutality and mass killings. The scalping campaign, which paid settlers and soldiers to kill any Mi'kmaq adult or child, was designed to drive the rebels from the land claimed by his king.

"The Board of Trade rebuked him for aggression and still more for overspending," says his entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

John Grenier, author of The Far Reaches of Empire, describes how Nova Scotia descended into a brutal, Vietnam-like war. Despite the official peace, superpowers France and England clashed in the remote province, while the Mi'kmaq and Acadians were chewed up in the middle.

"The war had bankrupted the colony," Grenier writes. "Parliament had authorized £39,000 for Nova Scotia in 1750, but Cornwallis had spent nearly £174,000."

The settlers were still largely confined to Halifax. Little farmland had been developed and the province relied heavily on supplies from England. The province was an expensive boondoggle — an "ill-thriven, hard-visaged and ill-favoured brat," as one critic later described it.

By 1752, Cornwallis was fed up with defending himself and sick of life in the colonies. He pleaded with London to let him come home. "At my setting out for this province, two or three years at most was the time I was to continue," he reminded his bosses.

He asked that "his majesty would be graciously pleased to allow of my resignation of the government and grant me the liberty of returning home."

He got his wish and left the war-torn province in the fall of 1752.

Cornwallis married in 1753, but his wife died a few years later without having any children. He spent his time with the "Corinthians," a dandyish troop of high-born bachelors. "In London, (Cornwallis) was well known as a leading man of fashion," MacDonald writes.

Duty beckoned and in 1756 he was ordered to join Admiral John Byng on a British fleet to relieve the garrison at Minorca, which was besieged by France.

The ships arrived, but didn't like their chances.

"To the horror of the brave garrison . . . the fleet sailed away, leaving them to their fate," MacDonald says.

Britain lost Minorca. "Cornwallis shared the odium," MacDonald writes. Byng was arrested and executed. Cornwallis was "almost torn to pieces by the populace" and burned in effigy. His high-placed friends saved him, but the ridicule continued. Newspapers ran cartoons lampooning Cornwallis as more concerned about fashion than fighting.

In 1757, he was ordered to join an expedition to attack the French port Rochefort. The mission faltered. Some saw the French as too strong and wanted to go home. Others said a bold attack could win the day. "Cornwallis unfortunately voted with his superior . . . and the expedition failed," MacDonald says.

This retreat brought more shame, but Cornwallis's royal connections again saved him. In 1762, he was dispatched to Gibraltar, the "most unhealthy station in Europe," MacDonald says. Over the coming years, he wrote letters to his friends in London, asking for promotion back to England. "No notice appears to have been taken of his request," MacDonald writes.

Cornwallis was only relieved of his post in 1776 when the war office marked him "DD" — discharged dead.

His family titles are extinct — the barony erased in 1823 and the earldom in 1852. "His name is fast coming under the category of 'Britain's forgotten worthies'," MacDonald concluded in 1899.

A century later, Cornwallis continues to fade.

Freelance Journalist and Author Jon Tattrie

When Governor Edward Cornwallis and his entourage founded Halifax in 1749, it was during a lull in the war with the Mi'kmaq. In fact, the Mi'kmaq greeted them with hospitality. One settler wrote home: "When we first came here, the Indians, in a friendly manner, brought us lobsters and other fish in plenty, being satisfied for them by a bit of bread and some meat."

The Mi'kmaq, although Cornwallis blamed it on the French, began to leave the area when he started to display designs against their land. At a meeting held in Cape Breton in the early fall of 1749 a British emissary told the Chiefs about their settlement plans for the province, which gravely alarmed the Mi'kmaq. Professor Jeffrey Plank, university of Cincinnati, remarks on the subject:

"...if the Micmac chose to resist his expropriation of land, the governor intended to conduct a war unlike any that had been fought in Nova Scotia before. He outlined his thinking in an unambiguous letter to the Board of Trade. If there was to be a war he did not want the war to end with a peace agreement. "It would be better to "root" the Micmac out of the peninsula decisively and forever." The war began soon after the governor made this statement."

If instead, the English had offered to make a reasonable land deal with the Mi'kmaq at this time everything could have been settled peacefully. But, they made no move to engage them in negotiations on any issue, let alone permission to settle on their land. Therefore, the Mi'kmaq renewed their declaration of war against them on September 23, 1749.

In response Cornwallis demonstrated how inhuman and ruthless he could be. On October 1, 1749, he called a meeting of Council aboard the HMS Beaufort; the following extract is taken from the minutes:

"That, in their opinion to declare war formally against the Micmac Indians would be a manner to own them a free and independent people, whereas they ought to be treated as so many Banditti Ruffians, or Rebels, to His Majesty's Government.

"That, in order to secure the Province from further attempts of the Indians, some effectual methods should be taken to pursue them to their haunts, and show them that because of such actions, they shall not be secure within the Province.

"That, a Company of Volunteers not exceeding fifty men, be immediately raised in the Settlement to scour the wood all around the Town.

"That, a Company of one hundred men be raised in New England to join with Gorham's during the winter, and go over the whole Province...

"...That, a reward of ten Guineas be granted for every Indian Micmac taken, or killed."

The horror contained in these words probably escaped the English. In their blind arrogance they could not see the unspeakable crime against humanity they had authorized. The next day, without conscience, the bounty was proclaimed by proclamation by Cornwallis:

"Whereas, notwithstanding the gracious offers of friendship and protection made in His Majesty's Names by us to the Indians inhabiting this Province, The Micmacs have of late in a most treacherous manner taken 20 of His Majesty's Subjects prisoners at Canso, and carried off a sloop belonging to Boston, and a boat from this Settlement and at Chinecto basely and under pretence of friendship and commerce. Attempted to seize two English Sloops and murder their crews and actually killed severals, and on Saturday the 30th of September, a body of these savages fell upon some men cutting wood and without arms near the saw mill and barbarously killed four and carried one away.

"For, those cause we by and with the advice and consent of His Majesty's Council, do hereby authorize and command all Officers Civil and Military, and all His Majesty's Subjects or others to annoy, distress, take or destroy the Savage commonly called Micmac, wherever they are found, and all as such as aiding and assisting them, give further by and with the consent and advice of His Majesty's Council, do promise a reward of ten Guineas for every Indian Micmac taken or killed, to be paid upon producing such Savage taken or his scalp (as in the custom of America) if killed to the Officer Commanding."

Thus, at a cost to his Majesty's colonial government's treasury of ten guineas per head, and at a cost to his servants of their immortal souls, the planned extinction of the Mi'kmaq was under way. It was an action no civilized nation would countenance, nor could any nation that undertook it be called civilized!

That aiding and assisting the Mi'kmaq was used by the English as an excuse to slaughter the French is attested too by Abbé Maillard, who kept a record of the Mi'kmaq declaration of war in Míkmaq and English. The following excerpt is translated from it:

"In 1758,while the King and his Ministers debated policy at Westminster in London, guerilla warfare intensified in the Maritimes, with English militiamen skirmishing with roving parties of Míkmaq and French soldiers. Captain John Knox witnessed some of the atrocities that seem to have become commonplace on the Acadian frontier. What follows is an excerpt from Knox’s war journal, which was not published until 1914. It describes an incident in which a party of French soldiers were taken prisoner by British colonials.

“And as there was a bounty on Indian Scalps (a Blot on Britain’s Escutcheon), the Soldiers soon made the supplicating Signal, the Officers turn'd their Backs and the French were instantly shot and scalp’d. A Similar Instance happened about the same time. A Party of the Rangers brought in one day 25 Scalps pretending that they were Indian. And the Commanding Officer at the Fort then Col. Wilmot, afterwards Gov. [Thomas] Wilmot (a poor Tool), gave Orders that the Bounty should be paid them. Capt. Huston who had at that time the Charge of the Military Chest objected such Proceedings both in the Letter & Spirit of them. The Col. told him, “That According to law the French were all out of the French [sic], that the Bounty on Indian scalps was according to law, and that tho’ the Law might in some Instances be strain’d a little yet there was a Necessity for winking at such things.” Upon which Huston in Obedience to Orders paid down £250, telling them that the Curse of God should ever attend such guilty Deeds“.

In the first paragraph of his sick proclamation Cornwallis cites various incidents as justification for its issuance. As far as I can ascertain it was only in the Americas where European colonial administrators would sometimes condemn to death an entire race of people for the actions of a few of their members. Imagine, holding innocent children responsible, and condemning them to die in an effort to try to terrorize adults into submitting to one's will!

Cornwallis, in a 1749 memorandum to the Lords of Trade requesting retroactive approval for actions he had already initiated, provides further proof of his insincerity and treachery towards the Mi'kmaq:

"When I first arrived, I made known to these Micmac, His gracious Majesty's intentions of cultivating Amity and Friendship with them, exhorting them to assemble their Tribes, that I would treat with them, and deliver the presents the King my Master had sent them, they seemed well inclined, some keeping amongst us trafficking and well pleased; no sooner was the evacuation of Louisbourg made and De Lutre the French Missionary sent among them, they vanished and have not been with us since.

"The Saint John's Indians I made peace with, and am glad to find by your Lordship's letter of the first of August, it is agreeable to your way of thinking their making submission to the King before I would treat with them, as the Articles are word for word the same as the Treaty you sent me, made at Casco Bay, 1725, and confirmed at Annapolis, 1726. I intend if possible to keep up a good correspondence with the Saint John's Indians, a warlike people, tho' Treaties with Indians are nothing, nothing but force will prevail."

Cornwallis cites everything but the real reason why the Mi'kmaq ended their brief cordial relations with the settlers. The omitted reason-and perhaps due his biases he was unable to recognize it-was that they had discovered that the British had come to seize more of their land and establish more settlements instead of making a lasting peace. Therefore, their disappearance from the site of Halifax at the same time the British were evacuating Louisbourg was only coincidental. The declaration of war made by the Mi'kmaq Chiefs in response to the seizure of ancestral lands attests to this.

The statement Cornwallis makes that "Treaties with Indians are nothing, nothing but force will prevail" provides a clear picture of the morally bankrupt people the Mi'kmaq had to deal with. His pretending to promote honour and good faith in dealings with the Mi'kmaq and other Amerindians while at the same time having no intention to act accordingly clearly reveals his own corrupt ethical standards and those of the system he represented.

The Lords of Trade responded to Cornwallis's letter in a memo dated February 16, 1750. They were not overly enthusiastic about the course of action he had chosen, for they cautioned him:

"As to the measures which you have already taken for reducing the Indians, we entirely approve them, and wish you may have success, but as it has been found by experience in other parts of America that the gentler methods and offers of peace have more frequently prevailed with Indians than the sword, if at the same times that the sword is held over their heads, offers of peace and friendship were tendered to them, the one might be the means of inducing them to accept the other, but as you have had experience of the disposition and sentiments of these Savages you will be better able to judge whether measures of peace will be effectual or not; if you should find that they will not, we do not in the least doubt your vigour and activity in endeavouring to reduce them by force."

Many apologists have claimed that the cruelties inflicted upon the Mi'kmaq and other Amerindian Nations were for the most part local acts of depravity and not acts sanctioned by the European Crowns themselves. However, this reaction by British officialdom towards Cornwallis's proclamation proves that contention wrong. By not rescinding or condemning his inhuman proclamation, the Lords of Trade, policymakers for the British government, showed support, thus implicating the British Crown itself in the crime of genocide.

The Lords also put into writing the paranoid fear the English had of Amerindians. It's embodied in the worry they expressed that the bounty on the Mi'kmaq might, "by filling the minds of bordering Indians with ideas of our cruelty,"somehow unite all the Amerindian Nations of the Americas against them in a continental war. The equivalent of such an impossible feat would have been the uniting of all the countries in Europe against an invader, which, based on their mutual dislike of one another, would have been impossible. However, what the Lords proposed might happen poses an interesting point. If the people of the Americas could have overcome their cultural differences and united, and if they had been heirs to a class-based, barbaric and warlike history similar to that of the Europeans, whom they may have outnumbered, most of the citizens of Europe today might be speaking a language imported from the Americas rather than the other way around.

On June 21, 1750, in what must have resulted from dissatisfaction with the number of Mi'kmaq scalps being brought in, Cornwallis's Council raised the monetary incentive by proclamation to fifty pounds sterling per head. It's interesting that Gorham himself was part of the Council which approved the 1749 scalp bounty, and he was also a member of the Council in 1750 when the bounty was raised. One might be excused for concluding that he was in a conflict of interest.

Professor Jeffery Plank, University of Cincinnati, comments:

Everyone involved understood the conflict to be a race war.... During the 1750s the politics of Nova Scotia centered on issues of national identity. At various times during the decade, the British engaged in combat with several different peoples who inhabited, or passed through, Nova Scotia: The Micmac, the French ... and the Acadians.... The British governors of Nova Scotia generally believed that they were surrounded by enemies, that the Acadians, the Micmac and the French would soon find a way to cooperate and overthrow British rule. One of the principle aims of British policy, therefore, was to keep these people separated, to isolate the Micmac, the Acadians, and the French. To achieve this goal of segregation, the colonial authorities adopted two draconian policies. In 1749 the governor began offering bounties for the scalps of Micmac men, women and children. The aim of this program was to eliminate the Micmac population on the peninsula of Nova Scotia, by death or forced emigration. In 1755 the British adopted a different but related strategy: it deported the Acadians, and relocated them in safer colonies to the west. Viewed in the abstract, these two programs, to pay for the deaths of the Micmac and to relocate and absorb the Acadians, represented very simple thinking. The colonial authorities who endorsed these programs placed the inhabitants of Nova Scotia into two categories, Europeans and savages, and treated them accordingly.

Quoted from Micmac History, by Lee Sultzman

The Micmac did not sign any peace agreement with the British that year. They had suffered a severe smallpox epidemic during 1747, and the French had accused the British of deliberate infection. Whether true or not, the Micmac believed the French and were so angry about this, they refused to make peace. In this decision, they had the full support of a French priest, Father Le Loutre (the new Rasles). Settlements at Chebucto and Canso were attacked during the summer of 1749. Especially galling to the British was the capture of an army detachment at Canso which later had to be ransomed from the French commandant at Louisbourg. The British refused to declare war reasoning that, since the Micmac were supposed to have submitted to British authority in Nova Scotia at the Treaty of Boston (1726), they could be treated as rebels, not enemies. In other words, no rules of civilized warfare. Offering £10 for every Micmac scalp or prisoner, Cornwallis dispatched the Cobb expedition with 100 men to hunt down and kill Micmac. In addition to the usual £10 for scalps or prisoner, Cornwallis offered an additional incentive of £100 for the capture of Le Loutre.

Cobb's expedition destroyed just about everything they found, but Micmac resistance only stiffened. By 1750 the price of scalps was raised from £10 to £50 which provided incentive for the formation of two additional ranger companies under Captains William Clapham and Francis Bartelo. During 1751 the fighting continued across the Chignecto Isthmus of Nova Scotia, but by summer Cornwallis ordered all ranger companies (except Gorham's) to disband. Too many strange scalps had been turned in for payment, including several which bore unmistakable signs of European origin. The French were still providing arms to the Chignecto Micmac - who were still dangerous and under the hostile influence of Father Le Loutre - but sending hired killers after them was never going to solve the situation. Cornwallis' decision ultimately proved correct, and in November, 1752 at Halifax, the Micmac signed a peace treaty with the British.

Unfortunately, the peace lasted less than two years...

This statue of Edward Cornwallis has been defaced many times over the years.

INGRIDBULMER / Staff Photo

1749 AND 1750

Statue of Gov. Edward Cornwallis

Cornwallis Park

Barrington Street, Halifax, Nova Scotia

For Daniel N. Paul, author of We Were Not the Savages

by Roger Davies

Cornwallis Must Answer!

Governor Cornwallis, loyal subject

of His Majesty George II,

how many murders makes

Nova Scotia English? How many

hunks of dried and bloodied skin

ripped from someone just then

picking berries or gathering clams

suffices the Crown? You stretch

evil taut, like a murderer’s

cord, over a land your blind eyes

can only see as wilderness or

the Imposition of State.

What accounting makes your

mind? Does the once tender

skin and shining hair come to

account in the “Account of

Scalps”? Don’t you think

a child’s Proof of Extermination

is worth an extra guinea or two?

It is the final solution,

after all.

Don’t be cheap, Governor.

And when did you and your

flowery language gangsters

dream up the beginnings

of biological warfare, putting

smallpox in blankets for

The People of the Land? The day will

come, Edward, when Cornwallis

Junior High will recognize you

for who you are and what you are,

instituting Mi’kmaq Holocaust Day,

when the children will surround

your obscene likeness in silence,

armbands of Mi’kmaq triangle designs,

in this place, sister to the Star of David.

Copyright: Roger Davies 2007

Halifax Herald - April 25, 2010

Hair ad raises ire of Mi’kmaq

Photo insensitive, Dan Paul says

Models With Hair Packets

By JON TATTRIE Special

A Halifax business is apologizing to Mi’kmaq people after running an advertisement featuring models holding human hair extensions in front of a statue of Edward Cornwallis.

Kevin Stanhope, the owner of Hairdressers’ Market Inc., said he had no idea that Cornwallis, the Englishman tasked with founding Halifax, offered a bounty for the scalps of Mi’kmaq men, women and children in 1749 and 1750.

"Whose statue it was, we knew nothing about. Absolutely nothing," he said Thursday.

Hairdressers’ Market sells hairdressing supplies and its ad in the April edition of Faces Magazine showed four young women laughing and holding packets of human hair.

Stanhope only discovered Cornwallis’s grisly past when Mi’kmaq people contacted him to ask him what he was thinking.

Stanhope, who is from New Brunswick, said he got the models to pose at the statue because it had multiple levels and was near his south-end business.

"Who would suspect? It’s a public park. If there’s such an offensive connection to it, why’s it there? Why aren’t there warning signs on it?" he asked.

Kyle Turk, publisher of Faces, likewise pleaded ignorance.

"I didn’t even know what that statue was. Obviously, we wouldn’t have published it if we had known."

He said the ad has been pulled from the May edition and would be taken off the website.

Dan Paul, Mi’kmaq historian and the author of We Were Not The Savages, was one of the people who contacted Stanhope. He said he was appalled when he saw the photograph and wanted to find out if it was created out of ignorance or racism.

After exchanging emails with Stanhope, he believes no racism was involved.

"I think it exemplifies the ignorance of Nova Scotia’s history," Paul said. "It was the actual hope of Cornwallis to wipe out the Mi’kmaq population on the mainland of Nova Scotia, which at the time included New Brunswick. You’re talking about most of the Mi’kmaq population."

Paul, who has long campaigned against the statue in Cornwallis Park near Halifax’s train station, described the governor’s explicit targeting of women and children as "sick in the extreme."

The plaque on the statue briefly outlines Cornwallis’s short career in Halifax but says nothing of the scalping proclamations.

Paul said that’s indicative of Nova Scotia’s "hidden history."

He compared it to the 1946 incident in which Viola Desmond was arrested for sitting in the whites-only section of a New Glasgow theatre.

The Dexter government gave Desmond, who was a beautician, a posthumous pardon this month.

"How many Nova Scotians knew that had happened? I would say very few, (outside of) the black population," Paul said. "Nova Scotia has diligently crafted an image that it is and has been for some time a racially equal society, which it wasn’t and to a large degree still isn’t. If it was, you wouldn’t see Cornwallis’s statue down at the end of Barrington Street.

"I’m not trying to erase his name from the history of this province. You can’t erase Hitler’s name from Germany’s history either but to continue to honour him is almost impossible to believe."

Paul said the incident points to a failure in the province’s education system.

"Are we doing a good job of teaching history to our children here in Nova Scotia? The answer is no. If you want to prevent the wrongs of the past from happening again, you have to teach the population about the past," he said.

Stanhope said he agreed with Paul. He’s ordering a copy of We Were Not The Savages and has signed Paul’s online petition calling for the removal of the statue.

Kings considers Cornwallis name change request

BY JENNIFER HOEGG

The Kings County Advertiser/Register March 31, 2010

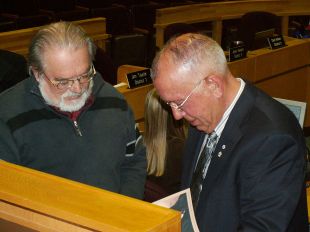

Dr. Daniel Paul, Member of the Order of Canada and

the Order of Nova Scotia, signs a copy of his book,

We Were Not the Savages

for Kings County Councillor Dick Killam.

The Cornwallis River winds through a large part of Kings County. Dr. Daniel Paul is leading a campaign to change the landmark’s name - and all others named for Governor Edward Cornwallis.

Paul spoke to Kings County’s committee of the whole (COTW) March 16 about the petition to rename all schools, streets, parks and other public areas named for the founder of Halifax because of his “attempted genocide” of the native population.

The author of is a leader and advocate for the Mi'kmaq culture: he received a honourary Doctor of Letters Degree from the University of Sainte-Anne in 1997 and is a member of both the Order of Canada and the Order of Nova Scotia. He appeared by invitation of the Race Relations and Anti-Discrimination Committee, in accordance with the municipality’s commitment to “promote respect, understanding, and appreciation of cultural diversity and inclusion of Aboriginals and racialized communities into the cultural fabric of the municipality.”

Addressing the past

Paul said the petition is “a project I have been working on for about 25 years.

“We really don’t know that a great deal of wars were fought here…. It’s a very long history and a very sordid history and very hard to condense it into a 20-minute presentation.”

However, he did provide councilors with extensive historical background.

“In 1749, Cornwallis came and set up shop in what is now Halifax,” Paul said. “He sent out emissaries to meet with Mi'kmaq chiefs to let them know Britain now owned Nova Scotia. They were now subjects of the king and had no property rights

In response, Paul recounted, the natives “renewed their declaration of war against the British on September 25, 1749.”

After Mi’kmaq attacked a group of British men in what is now Dartmouth that month, Cornwallis decried “perhaps it would be best to eliminate the Mi'kmaq all together,” Paul said, “and enacted a bounty for Mi'kmaq scalps men, women and children.” He wrote to British authorities to “exterminate the people and get rid of them in Mainland Nova Scotia all together.”

Considering the “cruel nature of what he had done,” the British worried it would encourage tribes to ally against whites. A bounty was set at 10 guineas per head at first, rising to 50 guineas in June of 1750.

Quoting Joseph Howe, Paul said, “the indians… had good reason for what they did. They were fighting for the country they loved.”

The Mi'kmaq had a good relationship with the French Crown, whose representatives first claimed what is now Nova Scotia in 1604. When Britain won the territory in 1713, a lengthy war began.

“You can’t go back, you can’t change history, you can’t take Cornwallis out of the history of Nova Scotia - but does he have to be idolized?” Paul asked. “Absolutely not.

“It’s not a civilized thing to do.”

Mixed reception

Councillor Chris Parker thanked Paul for his presentation and suggested to his colleagues, “if we were in a Germany, we wouldn’t have a street named Hitler Street, we wouldn’t have a river named Hitler River.”

“If our council wouldn’t sign the petition, I sure will”

“There were a lot of things in (the presentation) I didn’t know,” Councillor Dick Killam said. “But, over the years, I have sensed there were some big things in the background.” Killam said he also would sign the petition and he had visited the Annapolis Valley First Nations community to discuss the Cornwallis River, which flows through the Cambridge community.

"You can’t go back, you can’t change history, you can’t take Cornwallis out of the history of Nova Scotia - but does he have to be idolized? It’s not a civilized thing to do.” - Daniel Paul

“We definitely need to get the name Cornwallis out from their eyes, if possible.”

Councillor Wayne Atwater asked if Paul would be presenting to the Town of Kentville. Paul replied he was concentrating his efforts on Halifax Regional Municipality, but would welcome the opportunity.

“I want to commend you for your effort,” Atwater told Paul. “I’m just not one for signing petitions.”

After the presentation, COTW recommended council send letter to Kentville and the premier requesting they “deal with” the petition from Dr. Daniel Paul, and the petition be posted on the municipality’s webpage. “We recognize the fact the building is located in Kentville,” Deputy Warden Diana Brothers said before making the two motions, “but we represent 50,000 people outside town of Kentville, including two first nations, and I’m very aware of that.”

“I’m very proud of you people,” Paul said. “You have shown there are very forward-looking people in this country. We may be able to start a ball rolling here that will be unstoppable.”

Click to read American Indian Genocide

Please visit these URLs to read more about British barbarities

http://www.danielnpaul.com/AcadianMi'kmaqContactsOutlawed.html

A better understanding of the before mentioned can be had by reading: First Nations History - We Were Not the Savages - 2006 Edition

http://www.danielnpaul.com/BritishScalpBounties.html

http://www.danielnpaul.com/BritishScalpProclamation-1744.html

http://www.danielnpaul.com/BritishScalpProclamation-1756.html

http://www.danielnpaul.com/BritishGenocide-1759.html

http://www.danielnpaul.com/NewBrunswickCreated-1784.html

http://www.danielnpaul.com/WeWereNotTheSavages-Mi'kmaqHistory.html