|

|

|

|

April 8th, 2011

By Mark Stevenson

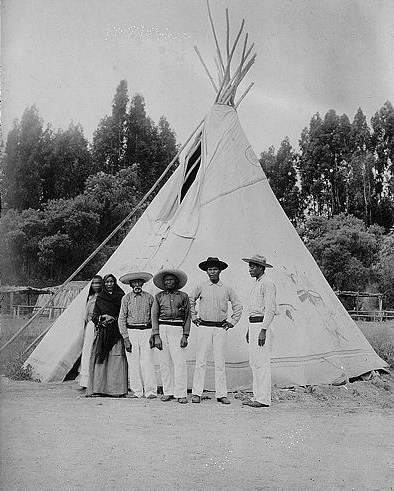

Yaqui Indians

As I blogged a few days ago, the repatriation movement (the return) of human remains and other items from museums and educational institutions to their rightful owners and communities continues to grow stronger.

The press reports that Northern Mexico’s Yaqui people buried their lost warriors after a two-year effort to rescue the remains from New York’s American Museum of Natural History, where they laid in storage for more than a century.

The burial on November 16 capped an unprecedented effort by U.S. and Mexican Indian tribes to press both governments to bring justice and closure to the 1902 massacre by Mexican troops that killed about 150 Yaqui men, women and children.

They would not be at peace with their souls and conscience until they got their people back to their land,” said Jose Antonio Pompa of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History.

The 12 skulls and other remains were buried in Vicam, a traditional Yaqui town in western Sonora state in Mexico.

The Pascua Yaqui tribe of Arizona took up the fight to have the bones returned.

“The approach we use is that we are one people . . . the border is just an artificial concept,” said Robert Valencia, vice chairman of the Pascua Yaquis.

U.S. Indian remains are protected under the North American Indian Graves Protection Act. But the law does not address Mexican remains held in the United States so the Arizona tribe contacted the Mexican Yaquis and they in turn contacted the Mexican government, which also decided to get involved.

Sidepoint – The remains were apparently collected by a U.S. anthropologist Ales Hrdlicka who hacked off the heads of the massacre victims and boiled them to remove the flesh to study Mexico’s “races.” He sent the resulting collection to the New York museum.

This “study” reminds me of the presumed science of phrenology in the 19th and 20th centuries in which the study of the shapes of skulls was thought to provide scientific evidence and different peoples and races. The surgeon general of the U.S. Army, for example, issued an order in about 1860 for U.S. soldiers to collect American Indian heads so these types of study could be conducted on American Indians.

Archaeology/Remains - Our Ancestor's Remains

By Mark Stevenson

Mexico City, Mexico (AP) 11-09

Northern Mexico’s Yaqui buried their lost warriors after a two-year effort to rescue the remains from New York’s American Museum of Natural History, where the victims of one of North America’s last Indian massacres lay in storage for more than a century.

The burial on November 16 capped an unprecedented joint effort by U.S. and Mexican tribes to press both governments to bring justice and closure to a 1902 massacre by Mexican federal troops that killed about 150 Yaqui men, women and children.

“They would not be at peace with their souls and conscience until they got their people back to their land,” said Jose Antonio Pompa of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History.

The 12 skulls and other blood-spattered remains interred in Vicam, a traditional Yaqui town in western Sonora state, carried some of the first forensic evidence of Mexico’s brutal campaign to eliminate the tribe.

As if the horror of the massacre weren’t enough, U.S. anthropologist Ales Hrdlicka came upon some of the bodies while they were still decaying, hacked off the heads with a machete and boiled them to remove the flesh for his study of Mexico’s “races.”

He sent the resulting collection to the New York museum. On Nov. 16, on the slope of a mountain near the Yaqui village of Vicam, the 12 sets of remains were “baptized” to give them names that have been lost to history.

They were given a warriors’ honor guard, and amid drumming, chants and traditional “deer” and “coyote” dances, each was laid to rest in the ground they had been striving to return to when they were slaughtered.

Perhaps best known for the mystical and visionary powers ascribed to them by writer Carlos Castaneda, the Yaquis fought off repeated attempts by the Mexican government to eliminate the tribe.

But they were largely defeated by 1900, and dictator Porfirio Diaz began moving them off their fertile farmland to less valuable territory or to virtual enslavement on haciendas as far away as eastern Yucatan state.

In 1902, about 300 men, women and children escaped from forced exile and started walking back to their lands in Sonora. They were stopped in the mountains near the capital of Hermosillo by 600 heavily armed soldiers, who attacked them from behind. What ensued, long known as “the Battle of the Sierra Mazatan,” is now considered one of the last large-scale Indian massacres in North America.

“What soldiers were doing was – instead of wasting ammunition – turning the rifle around and hitting people in the head who were down, to make sure they were dead,” said anthropologist Ventura Perez, who did a trauma investigation on the skulls for the American Yaqui tribes.

Some bore execution-style gunshot wounds to the back of the head. Cut marks on the bones indicated troops took ears as trophies, said Perez, a professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

The bones were forgotten in museum storage until Perez and anthropologist Andrew Darling, who works for the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona, started to study them in 2007 and realized their gruesome story.

The Pascua Yaqui tribe of Arizona took up the fight to have the bones returned.

“The approach we use is that we are one people ... the border is just an artificial concept,” said Robert Valencia, vice chairman of the Pascua Yaquis.

U.S. Indian remains are protected under the North American Indian Graves Protection Act. But because the law doesn’t cover Mexican remains held in the U.S., the Arizona tribe contacted the Mexican Yaquis and they in turn contacted the Mexican government, which also decided to get involved.

The museum agreed the bones and other artifacts – including blood-spattered blankets and a baby carrying-board from which Hrdlicka dumped an infant’s corpse – should go back, saying “cultural sensitivities and values within the museum community have changed” since Hrdlicka’s era.

Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History decided the real owners were the Yaquis and handed over the remains and artifacts last month for burial. The tribe held a memorial ceremony in a wood-paneled hall at the New York museum on Central Park with incense, drums and chants.

“This is the first time that the (natural history museum) has turned over cultural patrimony to a foreign government that immediately returned it to the indigenous people,” the museum said in a statement.

The remains were honored by Yaqui on both sides of the border, spurring the tribes’ hopes for recognition of their status as a single people who have long lived in both countries – in Sonora and in southern Arizona near Tucson.

The remains were packed into ceremonial wooden boxes and taken first to Tucson, where they were given a hero’s welcome by Pascua Yaquis, including an honor guard of Indian veterans of the U.S. Army.

“That is why the warriors’ role is important, because when we make territorial claims, it is because Yaqui blood was spilled there,” said Mexican Yaqui elder Ernesto Arguelles, 59. “This is the first opportunity we have had to stop and mourn.”

Click to read about American Indian Genocide